In Exodus 3, it says God is deeply concerned about the cries of our sisters and brothers. As Christians, we are to interrupt injustice, not lead the fight for it. Maybe God was too “woke” and didn’t understand our need to satisfy self-interest through injustice, poverty, persecution, and legislated discrimination. Maybe, His Word didn’t take into consideration that someday we would have to live out the Imago Dei – “all are created in the image of God.“ Could God really expect us to treat everyone with dignity, honor, and respect?

Let’s face it, focusing on others before ourselves, treating all people as equal, and trusting that the Word will transform hearts requires us to give up our controlling spirit. We all have an idea of what following Jesus should look like and who should be included. But if we’re honest with ourselves, our views are often influenced by our cultural values, politics, background, and what’s currently going on in the world around us. Maybe God was too woke to understand where we are today. How could He ask us to love our enemies!

Woke is a term that refers to awareness of issues that concern social justice. Originating in the 1940’s as “being aware of the truth behind things ‘the man’ doesn’t want you to know”. Today, in culture and politics, the most prominent uses of “woke” are as a pejorative. However, despite todays vagueness, you now see evangelicals, conservative activists and Republican politicians constantly using the term. That’s because that vagueness is a feature, not a bug. Casting a really wide range of ideas and policies as too woke and anyone who is critical of them as being canceled by out-of-control liberals is becoming an important strategy and tool.

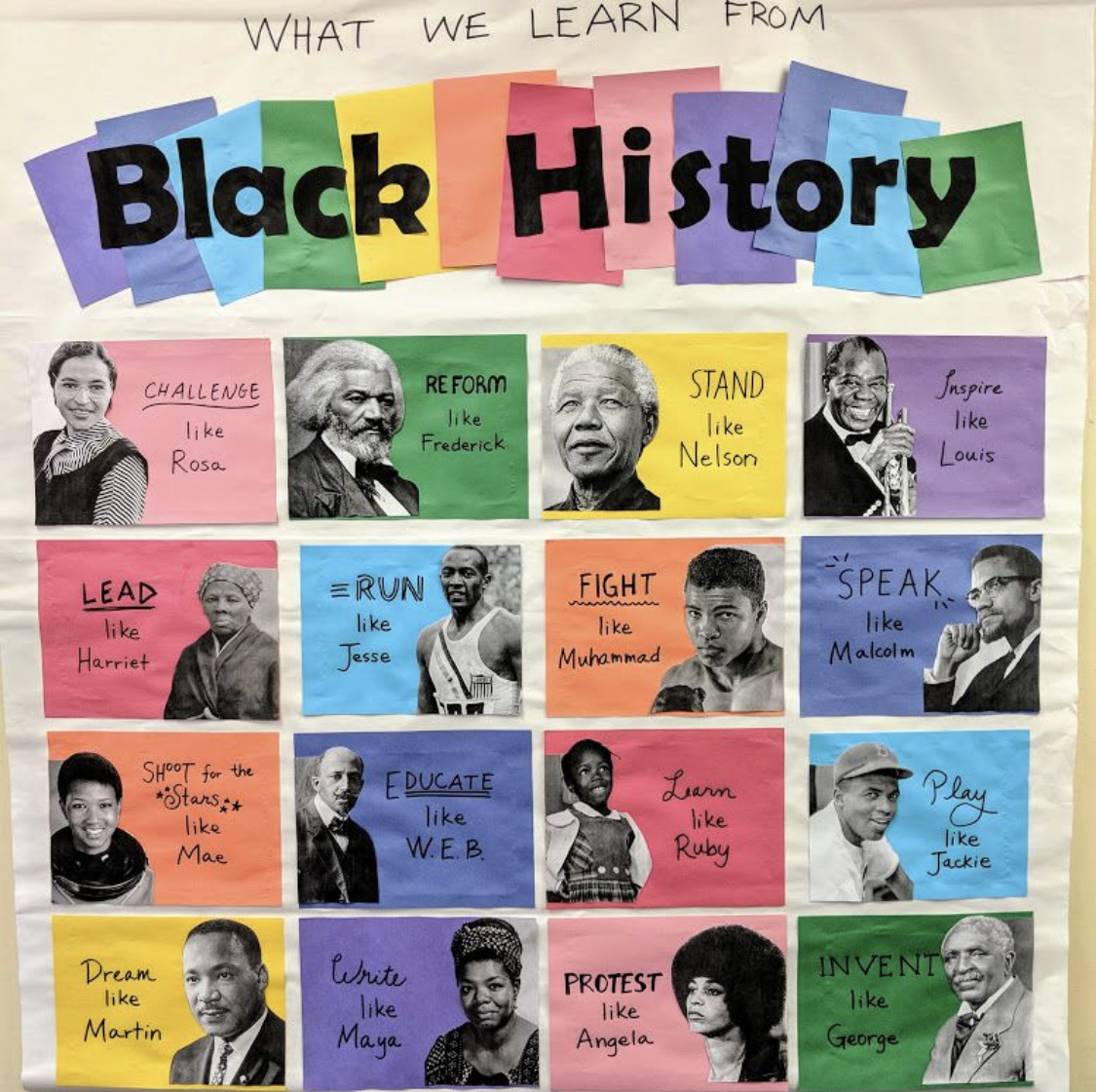

Some Christian leaders are using a blanket rejection to dismiss the realities of racism, implementing attempts to dictate the belief systems, definitions, authoritative binding, academic and ecclesiastical decisions regarding how race is to be communicated in the local church, school, and community.

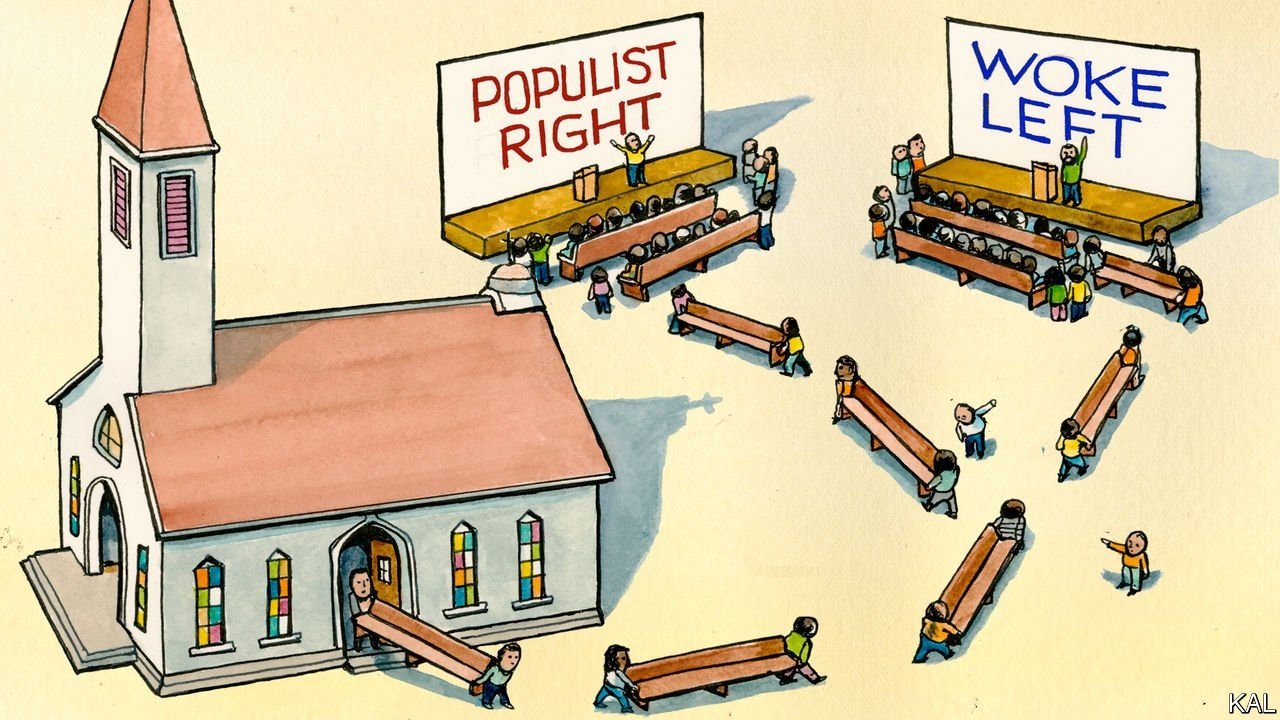

Ed Stetzer, a Southern Baptist and the executive director of the Wheaton College Billy Graham Center, says that churches have become increasingly politicized. “What’s happened is that people are now sorting themselves into churches that align more with their political ideology than their theology,” he said. “They want the sermons they hear on Sundays to align with what they hear on cable news all week.”

The controversy within the Southern Baptist Conference shines a light on the generational and ideological divides churches across the country are facing today. According to Ian Lovett of the WSJ, “one faction argues the SBC should step back from its role in electoral politics to broaden its reach and reverse a 15-year decline in membership. Another faction says the denomination has been drifting to the left, and the way to retain and attract members is to recommit to its conservative roots and stay politically engaged. Each side accuses the other of straying from the SBC’s core mission.”

Churches across America have come to provide further evidence of this political divide. Like the SBC, factions are not focused on what Jesus is focused on – love of neighbor, mercy, kindness, and grace. Instead, focusing on demands of political loyalty, disputes about racism, assigning the most negative labeling possible to those considered the enemy, and determining who is and isn’t “conservative enough.”

“It’s like someone is bleeding out on the floor,

and these guys are fighting over

how many pints of blood a person can lose.”

SBC seminary presidents organized a letter last year denouncing one of their major points of division, critical race theory—an academic set of assertions about structural racism across society that has been a flashpoint in the denomination. They and other conservatives acknowledge historic patterns of racism but don’t want it taught to their kids, talked about, or resolved. But they also say racism can have “structural forms.” Efforts to address the central issue being lifted up are met with gaslighting, denial, minimization, and ostracization.

Ve Lu of Nonprofit AF summarizes it this way, “So many of us are in denial. Not always denial like refusing to acknowledge what exists. More so, the subtle denial that we ourselves, who are Good People fighting for a just and equitable world, could further supremacy. After all, we weren’t involved in the acts of genocide at Kamloops or Tulsa, we tell ourselves. This is what makes white supremacy so potent. It is often subtle. It happens in ways we often don’t think about.”

The cognitive dissonance some guard elicits very negative responses to any attempt to discuss this subject. Breaking through the initial discomfort and rejection of this new information causes people’s defenses to go up, and they disengage. It’s not easy to swallow the realization that you are the transgressors of micro-aggressions on a micro-scale and that you have been unwitting participants in oppression on an aggregate/macro scale.

Church, we look disingenuous to the watching world. Our witness is being weakened as we are acting like the world. We are to be “in this world, but not of this world.” In John 17, Jesus asked the Father to

“sanctify them in the truth; your Word is truth.

As you sent me into the world,

so I have sent them into the world.

And for their sake, I consecrate myself,

that they also may be sanctified in truth.”

Jesus’s assumption in John 17 is that those who have embraced him and identified with him are sent into the world on a mission for gospel advance through disciple-making. His Word will go forth, and if you choose to represent Him your way instead of His, possibly it won’t happen through you.

Let’s determine to live as God desires—“to do justice, to love kindness, and to walk humbly with our God.”

Maybe God was and is “woke”, and sent His son to live out “wokeness.”